THE MISSOURI RIVER STEAMBOAT

Arabia

Compiled by

Margaret E. Gilbert, president and co-founder

MISSOURI RIVER

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPLORATION AND PRESERVATION SOCIETY

steamboatgranny[at]yahoo.com

In the very early 1800s, most people said that it was impossible to navigate the Missouri River. However, even before Lewis and Clark made their historic "voyage of discovery," French, Spanish, and to a lesser degree, British, adventurers had made exploratory journeys up and down the Missouri River with keel-boats, establishing trade with the native tribes that inhabited its shores. In 1819 the first steamboat to ascend the Missouri found it to be extremely challenging--the trip took 14 days to go about 200 miles from St. Louis to the village of Franklin, Missouri. And, later the same year, a government expedition took nearly four months to reach a point near present-day Fort Leavenworth. However, despite the perils of grounding on bars, an ever-changing channel, snags, and other obstacles, steamboats continued to push their way up the Missouri. At first they helped facilitate the rich fur trade with the native tribes. Later, pioneers by the thousands started their westward trek across the continent with a trip up the Missouri River on a steamboat. By the mid-1850s, steamboats were carrying all the necessities of life to the settlers on the western frontiers.

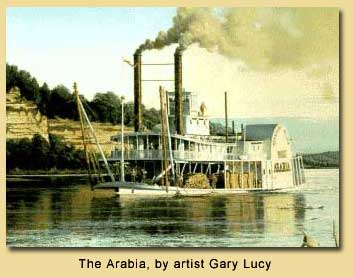

The ARABIA, built in 1853 by the Pringle Boat Building Company at Brownsville, Pennsylvania, on the Monongahela River, was a side-wheeler, 171 ft. long, 29 ft. beam, and 4.75 ft. hold. She could carry about 220 tons of freight, and was considered a medium-sized vessel for the Missouri. Twin 28-foot tall, side-mounted paddle wheels were driven each by its own engine. The steam that ultimately powered the boat created by burning wood and coal in the furnace located just beneath the nearly 25-foot long, iron-jacketed three-tube boiler. Fueling these boilers was no easy task, as the ARABIA could burn up to 30 cords of wood each day.

When built, she was owned by a group of Pennsylvania businessmen, and operated on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers prior to 1855. In February of that year, the boat was purchased by Captain John Shaw, of St. Charles, Missouri, for $20,000, and entered the Missouri River trade, running between St. Louis and St. Joseph, with some trips on to Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Pierre, Dakota Territory.

The Arabia's first trip on the Missouri took her to Fort Pierre with 109 soldiers from Fort Leavenworth, and supplies for Gen. Wm. S. Harney's expedition against the Sioux. She also ascended as far as the mouth of the Yellowstone River, 700 miles farther up-river, near the present-day Montana-North Dakota border. The trip took nearly three months. Sometime during 1855, cholera broke out on board the boat, taking at least three lives.

In the spring of 1856, the boat was purchased by Captain William Terrill and William Boyd. During the season, the ARABIA made at least 14 trips on the Missouri. In early March, 1856, a shipment of 100 rifles being sent to Kansas by the New England Emigrant Aid Company was seized off the ARABIA at Lexington, Missouri. When landing at Leavenworth on June 28, 1856, she was carrying a group of 25 abolitionists. The boat was boarded by the "Law and Order Patrol," who robbed the emigrants and sent them back down river.

According to a newspaper advertisement, the ARABIA departed from St. Louis on August 30, 1856, at 4:00 p.m., en route to Kansas, Weston, St. Joseph, Council Bluffs and Sioux City, with stops at intermediate ports. Seven days later, on September 5, 1856, she left Westport Landing in the afternoon, carrying 150 passengers, and more than 200 tons of freight, bound for her next stop--Parkville, Missouri. The ARABIA never made it to Parkville.

A huge snag pierced the ARABIA's thick oak hull, the tremendous impact throwing many of the passengers to the floor. Water immediately began pouring through the gaping hole in the hull and the boat sank to the bottom of the river (about twelve feet deep) in only a few minutes. Fortunately for those on board, the upper deck remained above water. There the nervous passengers waited for the steamer's single life-boat to ferry them, and what few belongings they could recover, to the safety of the river bank. The only casualty was a mule, thought to have belonged to a carpenter, which was tied to some sawmill equipment on the main deck, and forgotten in the panic.

The soft river bottom allowed the boat to sink so far that by the next morning only the smoke-stacks and top of the pilot house were visible. And those were soon swept away by the strong force of the river's current. Although one engine was removed from the boat not long after the sinking, none of the cargo was salvaged. Over a period of years, the river changed course, and floods deposited silt and debris over the top of the wreck.

Stories persisted for years that over 400 barrels of whiskey were on board when the ARABIA sank. In 1877, two Kansas City men dug for the wreck. After spending four months and $2,000 they recovered only one case of felt hats. Another group of men dug to the deck of the boat in 1897, attempting to recover the lost whiskey--but they came up dry. In 1975, Jessie Pursell and Sam Corbino spent many weeks and thousands of dollars trying to locate and excavate the ARABIA, but they never reached the boat.

In 1988, after consulting old river maps, and using a sophisticated metal detector, David Hawley of Kansas City located the wreck over one-half mile from the present channel, and 45 feet under a Kansas farmer's corn field. On November 13, 1988, the Hawley family began their excavation. It wasn't until November 30 that they found the top of one paddle wheel at 27 feet down. The bones of the drowned mule were uncovered on December 9. The Hawley's completed their dig in February, 1989. Nearly all the cargo was recovered, as well as the one remaining engine, the boilers, part of the rudder and stern, and other items. The snag which sank the ARABIA was also recovered.

Although the Hawleys originally started their quest as "treasure hunters," the tremendous cultural and archaeological significance of the artifacts recovered induced them to keep the treasures together in one collection which is now displayed in the Steamboat Arabia Museum located at 400 Grand Blvd, in the old river market area of Kansas City, Missouri. More information can be found at the museum's website: http://www.1856.com.